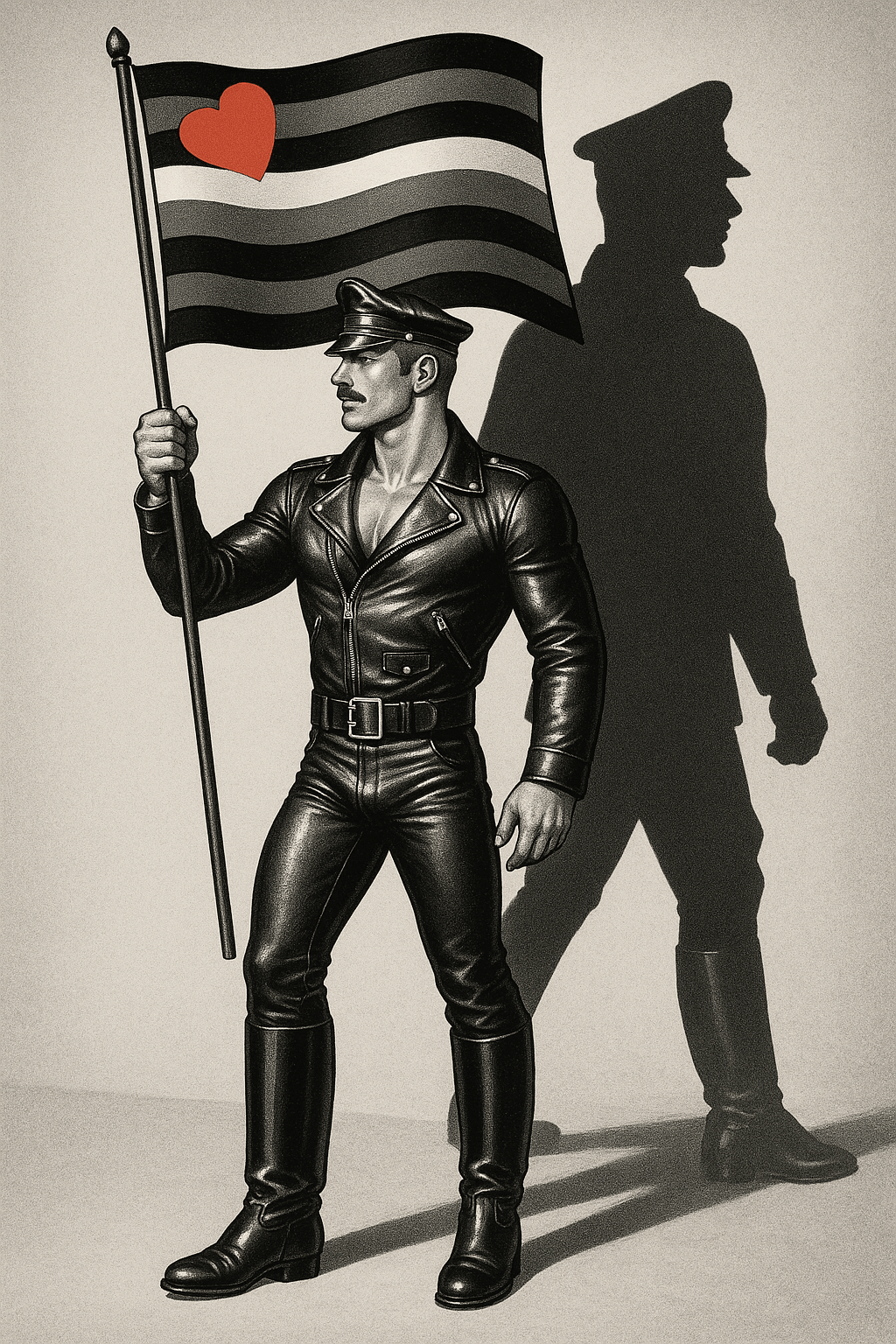

In a dimly lit backroom or under the blinding lights of a fashion week runway, the look is unmistakable: high-shined black boots, a tight leather jacket, peaked cap, perhaps even a Sam Browne belt crossing the chest. The silhouette is sharp, commanding, unmistakably masculine. It also evokes a history of uniforms worn by men who held power, whether in the streets or in the state.

It’s an image that resists easy interpretation. Is it erotic? Inevitable? Dangerous? Or is it something else entirely, something reclaimed, reframed, and worn as a kind of queer defiance?

These are not easy questions. Nor should they be.

Uniforms have always been designed to communicate control. Whether worn by soldiers, police officers, prison guards, or customs officials, they project order, discipline, and dominance. The tailoring is deliberate. The effect is psychological. The visual language of authority is not neutral; it is built to command. And it is often built to intimidate.

Design houses like Hugo Boss, which provided early templates for militarised fashion, understood this well. The crispness of a collar, the shine of a boot, the way a figure fills a uniform: these are not just about style. They are about hierarchy and spectacle, about bodies trained to obey and others forced to submit. But what happens when that uniformed figure appears not as a threat, but as an object of desire?

This question has haunted the gay imagination for decades.

After the Second World War, the hypermasculine figures drawn by Finnish artist Tom of Finland emerged as icons of queer liberation. His men, including leathermen, bikers, and cops, were not just sexually confident. They were composed, stylised, unapologetically masculine in ways that directly contradicted stereotypes of the “timid invert” or “effeminate pansy.” They wore the garments of power and wore them well. But they did not serve the state. They served fantasy.

For some, these images remain uncomfortable. They raise difficult questions about the eroticisation of control. Why would queer men fetishise the uniforms of those who once patrolled their lives, raided their clubs, enforced their invisibility? Why take on the image of the oppressor?

The answer, in part, lies in the long queer tradition of reclamation. The word queer itself, once a jeer, is now a declaration. The pink triangle, used to shame, is now a symbol of defiance. Drag turns gender parody into performance art. Leather culture turns fear into fetish, and erasure into embodiment. This is not about forgetting. It is about refusing to be small.

The postwar leather scene was not a pastiche of authoritarianism. It was a rebellion against moral conformity. Many early leathermen were working-class veterans, ex-cops, bikers, or closeted men who found in leather a coded language. The boots, caps, and jackets were not about allegiance to power. They were about visibility, masculinity, and control on their own terms. They allowed men to reclaim agency over their bodies and their desires in a world that sought to make them ashamed.

For many, the aesthetic is inseparable from the emotional architecture of BDSM. Dominance and submission are not simply roles acted out; they are relational frameworks built on trust, communication, and the consensual exchange of power. Uniforms signal this exchange clearly: one commands, the other yields. But within that dynamic lies an intensity that few other relationships offer. The man in uniform is not a tyrant. He is a fantasy construct of control, curated and consented to. For queer people who have lived under real, non-consensual systems of oppression, the ability to stage power, play with it, and ultimately control its context can be deeply cathartic. It transforms trauma into ritual, pain into play, history into theatre.

Still, the tension remains. The aesthetics of control do not lose their history just because we repurpose them. A police uniform might signify hot fantasy in one context, and state violence in another. A boot can arouse or terrify, depending on who wears it and who watches. The line between subversion and mimicry is narrow. Meaning is always in motion.

Perhaps what unsettles us most is the refusal of simplicity. We want our symbols to behave, to tell us clearly who is safe and who is dangerous. But queer history resists that neatness. It lives in the misread, the in-between. It thrives on the slippage between image and intent.

There is something undeniably powerful in wearing the look that once watched you from across the street or slammed your lover against a wall. It is not always a safe reclamation, and it is certainly not a neutral one. But it is a form of resistance. When queer people wear the garments of authority, they are not always paying homage. Sometimes, they are mocking. Sometimes, they are mourning. Sometimes, they are simply surviving.

The leatherman in tall black boots knows the weight of history. He carries it in the stitching, in the polish, in the posture. He knows how others might read it. But he dares to wear it anyway.

That is not comfort. That is complexity.

Author’s Note:

This essay is not a defence of any particular aesthetic, nor a condemnation. It is an invitation to think about power, memory, and desire. The answers may differ. The questions are what matter.

Footnote:

The terms “timid invert” and “effeminate pansy” reflect historical language used to pathologise and ridicule queer men in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “Invert” was a medicalised term from early sexology, used by figures like Havelock Ellis to describe homosexuals as psychologically or biologically ‘inverted’ in gender or desire. “Pansy” emerged in 20th-century slang as a slur against effeminate men, gaining notoriety during the so-called “Pansy Craze” of the 1920s and 30s. Both terms are invoked here critically, to underscore how leather culture and artists like Tom of Finland deliberately rejected these tropes in favour of new, assertive representations of queer masculinity.

It is important to emphasise that queer identity has never been singular, and that masculinity is not the only or superior way to be queer. While this piece explores hypermasculine aesthetics as a cultural and political response to historic stigma, it does so with full respect for the richness and diversity of queer expression. The author affirms a vision of masculinity that is expansive, inclusive, and free from hierarchy, one that honours femme, trans, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming voices as equally vital to queer liberation.

Leave a comment