There’s a certain inevitability to it. Mention the word “Leatherman” and most people conjure up the same tired images: a hypersexualised brute in chaps loitering at the edge of a crime scene, or a silent henchman lurking in a villain’s lair. On screen, we’ve been portrayed as monsters, murderers or punchlines. Rarely as men.

But the Leatherman is more than a camped-up caricature or a lazy BDSM bogeyman cobbled together by a costuming department. He is part of a subculture, a brotherhood, an erotic identity and, yes, sometimes a fashion statement, but never just a trope. The way we appear in film and television has long mirrored the treatment of queer life more broadly: misunderstood, stigmatised or scrubbed clean for the comfort of straight audiences. To understand the Leatherman on screen, you have to understand who he is when the cameras aren’t rolling.

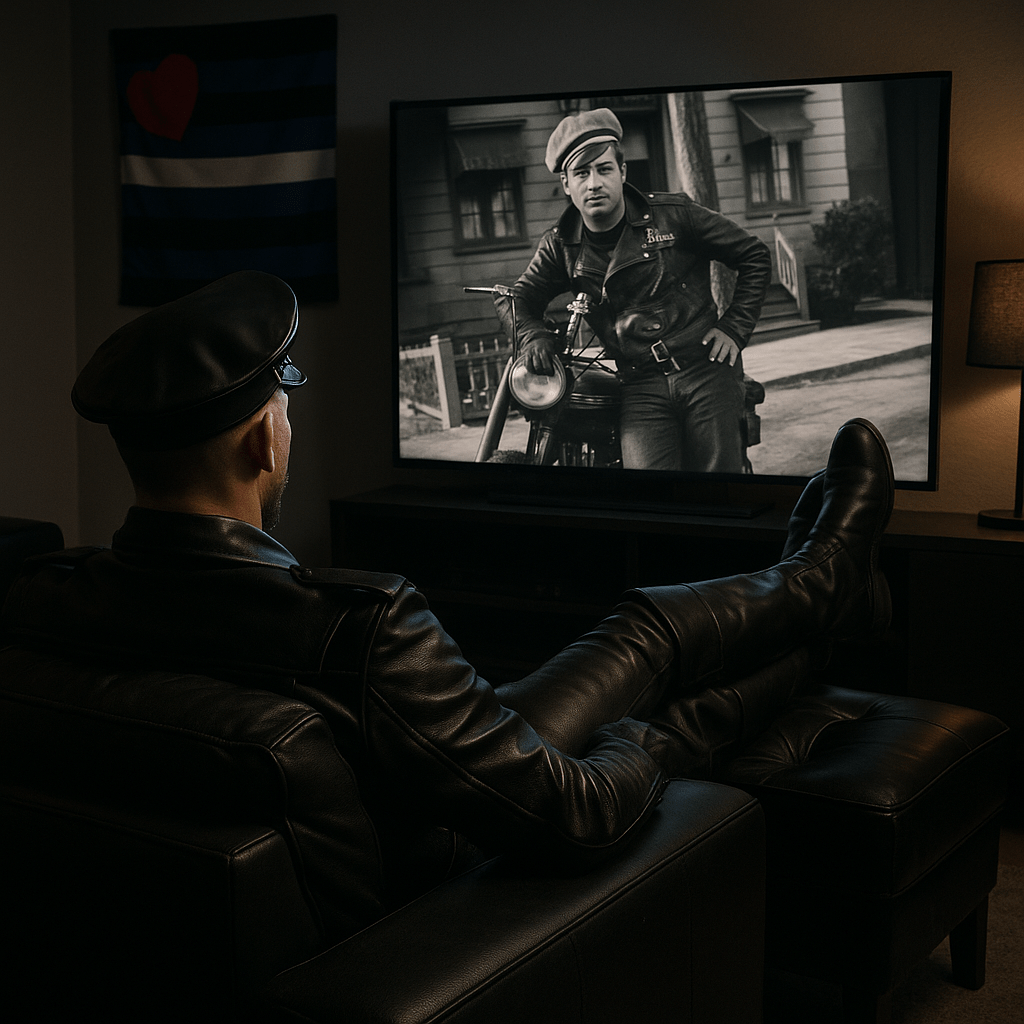

Before the leather scene had a name, its iconography had already begun to take shape. Think of Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953): leather cap, black biker jacket, detached cool with a hint of menace. Or James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, all repressed energy in a red windbreaker. These weren’t queer films, not explicitly, but the styling was drenched in a kind of homoerotic possibility. It was masculinity, stylised, defiant and often simmering with something unsaid.

The leather subculture, as it came to be, was forged in the aftermath of war. Gay men, many of them former servicemen, returned home and sought belonging in biker clubs and leather bars. These weren’t just places of sex and spectacle, though they were proudly those too. They were spaces of community, kinship and survival. This was masculinity reclaimed by those who were told they didn’t deserve it. You wouldn’t know it from watching telly.

What’s even less visible, and no less important, is the absence of racial diversity in how leathermen are portrayed. While Black, Latino and Asian men have always been part of leather culture, their presence on screen has been largely erased. The leatherman, when he does appear, is almost always white and often coded as working-class, but only in a very particular, sanitised way. It is a whitewashing of a subculture that was never monolithic.

One place Leatherman history found visual form was in the drawings of Tom of Finland. His art, while fantastical, was also deeply grounded in the lived erotic imagination of leather men: proud, muscular, moustachioed and unashamed. These images were lifelines to many queer men during decades of invisibility. But when cinema adopted his aesthetic, it too often twisted it into something grotesque.

Leather in mainstream film has long stood in for menace, danger or deviance. Take Pulp Fiction (1994), where the gimp, silent, masked, restrained, is shorthand for the unspeakable. The scene is infamous, not only for its violence but for how it fuses leather with sexual horror. It flattens an entire culture into a visual punchline.

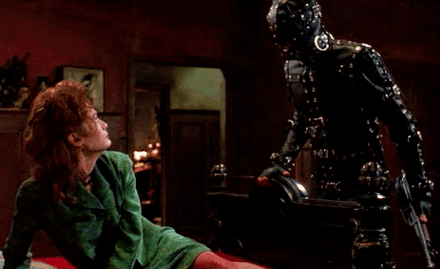

Or consider The People Under the Stairs (1991), where the leather-clad character known as “Daddy” is a child-tormenting tyrant. His queerness is suggested but not spoken, expressed entirely through leather, surveillance and sadism. It’s a caricature that says more about the filmmakers’ fear than about the real world.

A scene from the Blue Oyster Bar in the 1984 film Police Academy.

And then there’s Police Academy (1984), where the Blue Oyster Bar scene plays out again and again across sequels. It’s meant to be funny , the hapless straight lads stumbling into a leather bar and getting an unexpected dance from men in uniform. But the joke isn’t about joy or community; it’s about panic. The leather men aren’t characters. They’re props used to humiliate.

There have been attempts to course-correct, if not always convincingly. James Franco’s Interior. Leather Bar. (2013) reimagines the “lost” 40 minutes of Cruising, blending documentary and artifice in a project about boundaries, authenticity and kink. It is flawed and, at times, indulgent. But to its credit, real leathermen were involved in the process. Franco may have worn the harness, but others brought the meaning. For once, the community had a say.

Stronger still are the documentaries and independent films that allow leathermen to speak for themselves. Works like Mr. Leather, The Legend of the Underground and Kink offer portraits that are complex and defiant. These aren’t cautionary tales. They’re stories of ritual, love, ageing, power and care. They show leather not just as sex, but as language and community.

One subject largely absent from these depictions is the impact of AIDS. While the broader queer community has seen its story told, often clumsily, occasionally beautifully, the leather community’s response to the epidemic is still mostly left out. This erasure is striking, given how visible leather men were in the 1980s and how central they were to the creation of safer sex education and mutual care networks. Leather communities didn’t just endure the crisis; they organised, mourned and resisted through it. But film and television have rarely made space for that legacy, opting instead to disappear us from the frame entirely.

And we need to be clear: leather isn’t the sole preserve of gay men. Straight men, in heavy metal, punk and biker cultures, have long worn leather as a symbol of rebellion and virility. Rob Halford of Judas Priest, openly gay and proudly leathered, became an icon embraced by straight fans who didn’t always realise where his look came from. Countless straight men have mimicked the aesthetic. Fewer have understood the politics behind it.

That crossover creates tension. Sometimes it’s respectful. Other times it strips the imagery of its queer origins. Leather becomes just a look, emptied of its context, its defiance, its history.

Media doesn’t just reflect culture; it shapes it. Every time a leatherman is shown as violent, mentally unstable or perverse, it reinforces suspicion. Every time we are erased from queer storylines, we are told we don’t belong. And often, we are missing entirely. We’re too masculine to be camp, too kinky to be mainstream, too working-class to be aspirational.

But we are here. And we are not all the same. Not every leatherman is dominant. Not every leatherman is gay. We are older, younger, Black, brown, disabled, gentle, loud, introverted, nurturing. Some of us served in the army. Some of us work in care. Some of us, believe it or not, quite enjoy Strictly.

Representation matters because it opens doors, not just for how others see us, but for how we see ourselves. For leathermen, that means not just being included, but being shown honestly. It’s time to retire the gimp suit and the cheap punchline. We’ve spent too long in the shadows. Give us the light, and let us take up space.

Fashion, as ever, has been quicker than film to flirt with the edge, and sometimes to cash in on it. DSQUARED2’s Spring/Summer 2025 “Obsessed2” collection sent models down the catwalk in harnesses, jockstraps, biker caps and leather chaps, in a clear homage to Tom of Finland’s illustrations. It was all very knowing, very stylised and very safe. The designers described it as a “soft Tom of Finland”, a palatable fantasy reworked for the front row. Whether it was tribute or pastiche is up for debate, but it speaks volumes that the leatherman is now seen as fit for high fashion, even if he’s still too much for primetime telly. If fashion wants the look, it should learn the history too.

Mainstream media still finds it easier to parody than to portray. The leatherman remains a convenient shorthand, for deviance, comedy, or menace, rather than a complex figure with history, heart and community. This blog is not here to flatter stereotypes, but to stretch the frame. If the screen keeps narrowing the lens, then let this space widen it. By filling in the gaps left by commercial storytelling, we honour the lives, cultures and aesthetics that shaped us, and continue to shape queer identity today.

Leave a comment