In the UK, what you do in your bedroom could still get you arrested. If you’re gay, the risk is higher. Suppose you’re a leatherman, higher still. And if your desires involve floggers, clamps, needles or branding irons, even when everyone involved is a consenting adult, then you might be flirting not just with pain, but with criminal liability. That’s not a relic of Victorian law books. It’s the legacy of Operation Spanner and the ruling in R v Brown, where a group of gay men were convicted for sadomasochistic sex acts that took place in private, with full consent. Just a few years later, in R v Wilson, a heterosexual man who branded his wife’s buttocks with a hot knife was acquitted because it was a private matter between a loving couple. The law claimed it wasn’t about sexuality. But when you look at who was punished and who was not, it’s hard to conclude that the social mores of the time had nothing to do with it.

I didn’t come to Spanner through activism or headlines. I heard about it in a fetish club, muttered with the kind of weight that makes you put down your pint. You think you know what the law protects, what consent means. Then someone tells you that in 90s Britain, a group of men were arrested, charged, and convicted for hurting each other, with permission. And that the courts decided their consent was meaningless.

What deepens the wound isn’t just the judgment from the courts or the headlines. It’s the slow, silent way that shame creeps in when your desires are understood only by their distance from acceptability. When the law says your pleasure is a public danger, it doesn’t need to shout. It just plants the idea that your tastes are something to be managed, softened, tucked discreetly out of sight. And even if you push back, even if you know better, that shame doesn’t vanish. It lingers. It mutates. It colours how you walk into a sexual health clinic, how you speak in a team meeting, how you name, or don’t name, what you love.

As a leatherman and a psychiatrist, I live in the overlap of disciplines obsessed with boundaries. Pleasure and pathology. Risk and responsibility. As someone who’s just completed a postgraduate certificate in mental health law, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about consent, its legal weight, its moral dimensions, and in the context of exploring LGBTQI rights for this blog, the strange ways it collapses under the wrong gaze.

Operation Spanner began in 1987 when police in Manchester stumbled across a series of homemade videos depicting consensual sadomasochistic acts between adult men. Alarmed by what they found, they escalated the investigation nationally. Raids followed. Dozens of men were questioned. Sixteen were ultimately prosecuted. Their crime? Engaging in private BDSM, flogging, piercing, and branding, with full awareness and agreement. The footage was raw, yes, but it was negotiated, filmed with trust, and shared only within circles of consent.

But that didn’t matter. At trial, the judge, James Rant, dismissed consent as irrelevant. He said, and this stayed with me, “People must sometimes be protected from themselves.” The men were convicted of assault occasioning actual bodily harm and sentenced to prison. Their private pleasures were reframed as public violations.

When I reviewed the case out of curiosity, I couldn’t help but hear the echoes of old psychiatry, of Krafft-Ebing, of Freud, of decades spent medicalising desire and branding deviance as disorder. What Rant delivered wasn’t a judgment about law, not really. It was moral paternalism. He was not prosecuting harm. He was prosecuting non-normativity. The whips, the clamps, the scars, these were just props. The real offence was being aroused by them.

The men appealed, of course. All the way to the House of Lords. But in R v Brown (1993), the Law Lords upheld the convictions in a 3–2 split. They ruled that one cannot consent to actual bodily harm unless it falls within a legally sanctioned context -surgery, sports, tattooing. BDSM did not qualify. Pleasure, it turns out, is not a defence.

Eventually the case made its way to the European Court of Human Rights (Laskey, Jaggard and Brown v United Kingdom, 1997). Here, the argument shifted to Article 8 of the European Convention, the right to respect for private and family life. But even the ECHR found against the appellants. The state, they reasoned, has a right to interfere in private acts when public health or morality is at stake. The irony, of course, is that no one was harmed except in the ways they chose to be, and in the ways the state later imposed upon them.

This is where things get interesting. The European Convention is a “living instrument.” It is interpreted by the Court in the context of evolving social standards. That phrase, living instrument, stuck with me during my training. It’s both hope and warning. Hope, because laws can grow. Warning, because they can grow in the wrong direction, too. Just look across the pond at Trump’s USA.

Since Spanner, social attitudes have shifted. Kink is no longer exclusively the stuff of dim basements and whispered parties. Fetish communities are more visible. Consent frameworks like SSC (Safe, Sane, and Consensual) and RACK (Risk Aware Consensual Kink) – born from the movements and protests that Spanner generated- have matured. And yet, the R v Brown precedent still stands. You can still be prosecuted in the UK for engaging in consensual acts that result in bodily harm, even if every party involved begs to differ.

That’s a legal and ethical dissonance I find hard to stomach. In mental health law, we’re taught to uphold patient autonomy wherever possible. To presume capacity. To understand risk in context, not in isolation. We respect the right of patients to make decisions others might find unwise, provided those decisions are informed and voluntary.

And yet, when it comes to kink, the law still infantilises. It decides for us what we are allowed to want. And if what we want leaves a bruise, it denies that we ever truly chose it.

The impact of Spanner wasn’t just legal. It was cultural. It told queer men, especially those in the leather and BDSM communities, that their desires were dangerous, criminal, and unprotectable. It sowed mistrust in law enforcement, in courts, in the very idea that our private lives could ever be truly ours. And it made visible something that psychiatry, too, has long done: the erasure of consent in favour of imposed order.

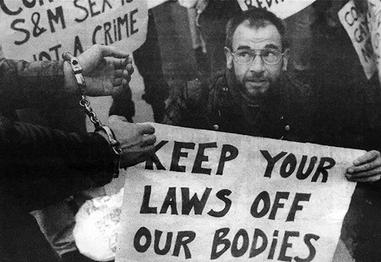

But resistance grew. Spanner sparked protests, pamphlets, legal reform movements. It galvanised organisations like the Spanner Trust. And it gave rise to Pride marches where kink was not hidden but marched front and centre, as it always had been, from the very beginning.

I don’t know whether the European Court, if presented with a case like Spanner today, would rule the same way. I hope not. I believe not. The living instrument must evolve. And so must our laws, our ethics, our professions.

Operation Spanner was not an aberration. It was a mirror. It reflected what the state fears, what the public scorns, and what the law is willing to punish in the name of decency.

As a psychiatrist, I’m told to listen to people’s stories, not rewrite them. As a proud leatherman, I listen to my body and trust its truth. And as someone who has studied the law, I’m learning that consent, while powerful, is not yet enough. Not when desire looks like mine.

Thanks for reading. Please consider subscribing.

Leave a comment