I turned to Catholicism searching for solace from queer shame, but found deeper contradictions. Humanism, not doctrine, offered me dignity, reason, and a vision of humanity worth believing in.

It’s a dangerous fiction that Christianity emerged out of nothing: untouched, unprecedented, pure. Like every major religion, it is the product of historical layering, mythic recycling, and cultural adaptation. The virgin birth? A motif older than the Gospels. Horus of Egypt, Dionysus of Greece, Mithras of Persia,each had miraculous origins, god-bloodline destinies, and ritual followings. The resurrection? A rebranding of a far older story arc: the god who dies and returns, from Osiris to Tammuz to Persephone. Even the Eucharist,body, blood, bread and wine,finds echoes in earlier rites, from Dionysian feasts to Mithraic banquets beneath Roman streets.

What Christianity did, with ruthless ingenuity, was co-opt and consolidate. It swallowed the winter solstice and named it Christ’s Mass. It rebranded spring fertility festivals as Easter, named after the goddess Ēostre. Pagan temples became churches. Local deities became saints. This wasn’t mere coincidence; it was cultural colonisation masked as divine mandate. And that mandate has long been weaponised.

Because once a mythology becomes institutionalised,once it declares itself not just a truth but the truth,it begins to exert power. Not just spiritual power, but political, social and psychological. Christianity did not spread across Europe by gentle persuasion alone; it marched with empires, crowned kings, justified conquest, and built laws in its own image. And those laws linger.

You can trace the lineage from Church fathers condemning “sodomites” to modern legislatures denying queer people the right to marry, adopt, exist. You can hear echoes of biblical purity in conversion therapy clinics, in the closets that still hold fear, in the pulpits that preach shame dressed up as salvation. All in the name of a mythology that borrowed freely from other traditions,and then declared them heresies.

This is the dark alchemy of religion: it takes archetypes that could unite us and retools them to divide. It builds temples not just of worship but of hierarchy. And for centuries, LGBTQ+ people have been cast out into the wilderness beyond those gates. To call Christianity a mythology is not to strip it of meaning; it is to level the playing field. To acknowledge that stories are not inherently oppressive, until institutions decide who gets to tell them and who must be silenced.

I say all this not as an outsider lobbing stones at stained glass, but as someone who once went looking for shelter inside it. I wasn’t raised with religion. It wasn’t part of my cultural scaffolding or childhood routine. I found my way to Catholicism in young adulthood, at a time when I was living with profound shame and internalised homophobia,when being gay felt like something to be hidden, managed, maybe even cured. I was looking for answers, for a sense of belonging, for a way to make peace with myself.

And at first, I found something beautiful: a community that was, on the whole, warm and welcoming. There was ritual, solidarity, quiet reflection. I saw people trying to live with compassion and purpose. It was not brimstone and damnation, but something far gentler,and that made the contradiction harder to name. Because alongside all the talk of love and grace, there was still the unspoken understanding that people like me were fundamentally disordered. That my desire was something to be resisted. That my existence, while tolerated, would never be fully affirmed.

It’s a strange thing, to be tolerated. It’s a holding pattern: neither condemned outright nor truly embraced. I sat in pews where I was told to love my neighbour, but never myself. I prayed for clarity and found only compromise. The message, however softly spoken, was clear: to belong here, you must diminish yourself.

Eventually, I couldn’t do it anymore.

That rupture led me toward humanism,not in a moment of rage or rejection, but in quiet, deliberate steps. Humanism gave me language for what I already sensed: that our moral worth doesn’t come from divine decree. That compassion doesn’t require commandments. That love,queer love, messy love, all of it,is not a sin, but a fundamental expression of what it means to be human.

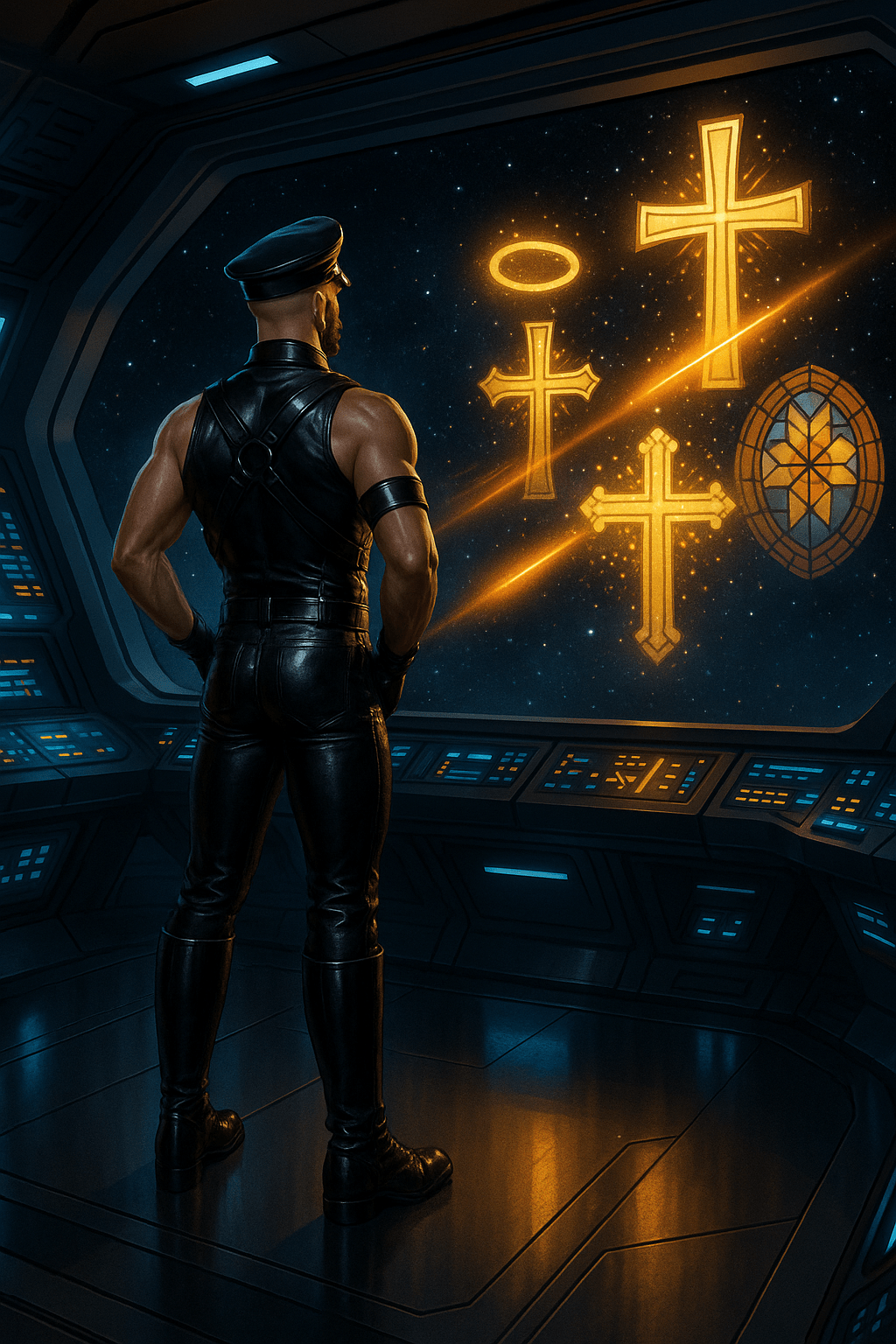

For me, this wasn’t just about abstract ethics. It was about coming into my own as a gay man,not just in private identity, but in the fullness of queer culture and community. I am a Leatherman. I found pride and purpose not in penitence but in embodiment, in connection, in the joyful complexity of our desires. Leather gave me a language of intimacy and trust, of resilience and care, that no church ever offered. It taught me that there is no shame in knowing who you are, only courage in living it.

Humanism, to me, is not about tearing things down. It’s about building something better: a worldview rooted in empathy, evidence, and the dignity of all people. It doesn’t ask you to renounce wonder,only to seek it in the world as it is, not in myths but in one another. It doesn’t pretend we’re fallen and broken; it recognises we’re unfinished, always evolving, always trying.

What I clung to, more than scripture, was Star Trek.

I was a Trekkie long before I flirted with Catholicism, and the vision of humanity portrayed in the Federation stayed with me far longer than the catechism ever did. The Federation wasn’t perfect, but it embodied a principle that struck me as profoundly moral: that humanity, at its best, should strive to better itself,not out of fear of divine punishment, but because it is the right thing to do.

In the world of Star Trek, human beings want for nothing. Food, shelter, education,all needs are met. And in that context, the old engines of division,money, greed, hoarding of resources,lose their power. Freed from survival anxiety, people turn toward exploration, collaboration, curiosity. They strive not for dominance, but understanding. Not for salvation, but solidarity.

That, to me, is the humanist vision.

Humanism embraces the idea that we can do better,not because we are commanded to, but because we care to. It rejects the dogma that divides and the doctrines that punish, and it turns instead toward the messy, urgent, hopeful work of building a world in which every person can live with dignity. A world where basic needs are not privileges. Where difference is not punished. Where existence is recognised for what it is: fleeting, precious, and worthy of joy.

Starfleet’s optimism might be fictional, but the longing it taps into is very real. We do not need to be governed by myth to be moral. We do not need to be threatened with damnation to be good. We just need to believe that a better world is possible,and to get on with the business of building it.

Leaving religion didn’t strip my life of depth. If anything, it added more. Because once you let go of the idea that there is a cosmic plan,that some lives are “blessed” while others are “broken”,you begin to see the full, messy, beautiful reality of humanity. No more justifying injustice as divine will. No more pretending love needs to be straight to be sacred.

I’ve come to see religion not as a divine gift, but as a survival strategy: a structure humans built to organise power, enforce conformity, and soothe the terror of mortality. And like any structure, it can be used for good,but it also demands scrutiny, especially when it masquerades as moral authority while denying dignity to so many.

Queer people know this better than most. We’ve been the scapegoats, the heretics, the sinners. We’ve been cast out so that others can feel saved. And still, we endure,not by divine grace, but by each other. That, to me, is sacred. May you find freedom, purpose, and pride in your own journey. Live fully, love boldly, and as Spock might say “live long and prosper”.

Leave a comment