The government wants to make the internet safe. And who could disagree with that? As a gay man, a leatherman, and someone who came of age when the only sex education we got was Section 28 and silence, I more than most understand the cost of exposure without explanation. Young people deserve better. They deserve protection from online predators, misogynists, incels, fundamentalists, porn peddlers and far-right agitators. The Online Safety Act 2023, we’re told, is here to protect them from all that. A noble ambition. But like so many well-meaning laws, it risks stumbling into something altogether more dangerous: the slow erasure of adult life in public, and with it, the sanitisation of queer, kink and fetish visibility.

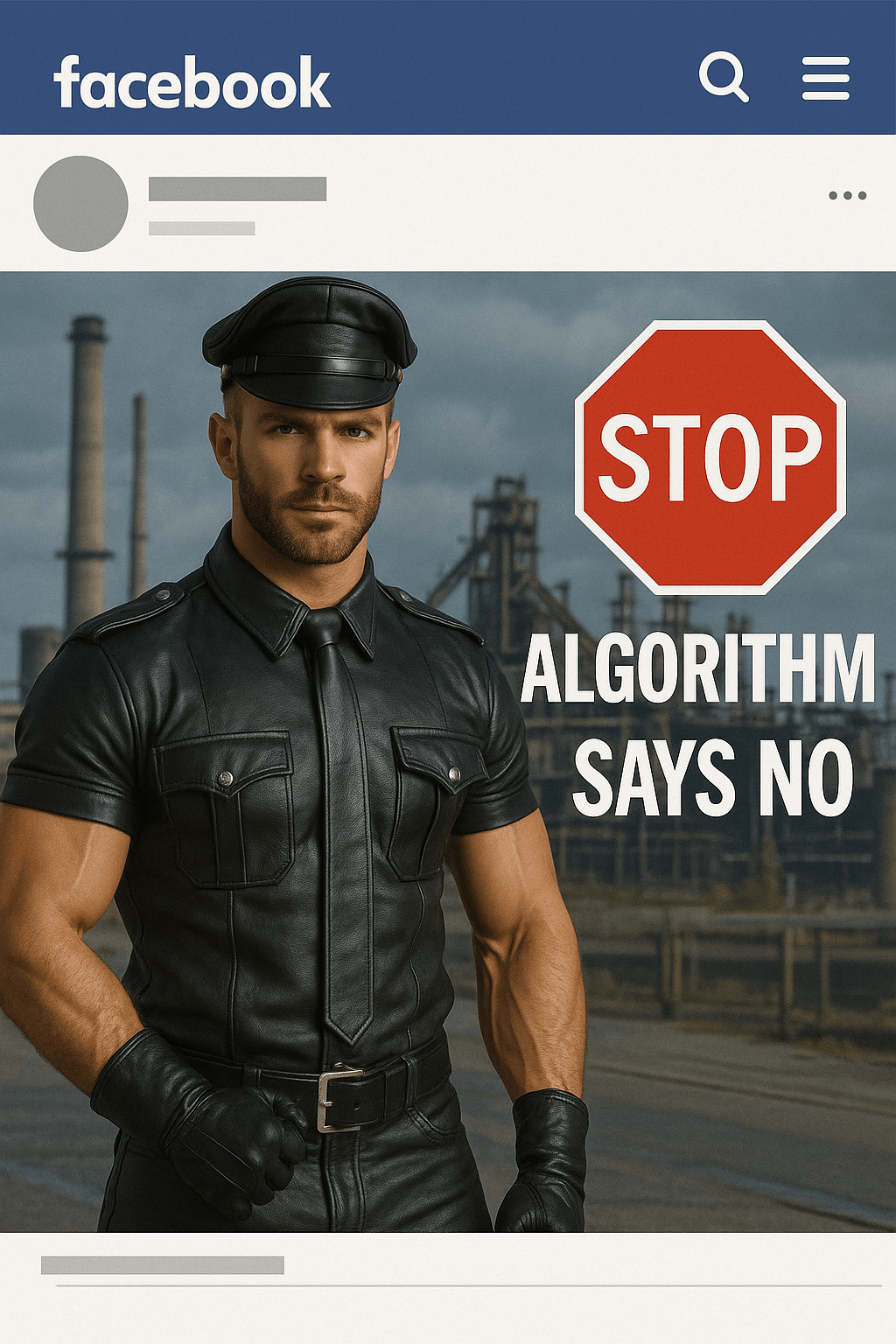

This isn’t a conspiracy theory. It’s a regulatory reality. The Act places expansive duties on online platforms to monitor, moderate, and pre-emptively remove content deemed harmful, not just illegal, but “psychologically distressing” or “potentially harmful to adults.” A vague and amorphous category if ever there was one. It’s not hard to imagine how this plays out in practice. A photo of a man in leather, posted with pride after a community march, is suddenly in violation of Instagram’s slippery standards. A discussion thread on BDSM safety practices disappears. An educational post about consent and power dynamics is shadowbanned.

And always, always, the justification is the same: think of the children.

Let’s be clear: I am not advocating that fetish content should be broadcast without restriction or nuance. But leather is not pornography. Fetish isn’t abuse. And a man in full leather, posted on Instagram to celebrate his pride or community, is not inherently harmful. Yet under the Act’s vague guidance around “content harmful to adults” and the expanded obligations on major platforms to pre-emptively filter, moderate, and remove risk, this is precisely the kind of content that vanishes first.

The state, in its moral panic, risks throwing out the teachers and leaving the groomers. Because communities like mine, the fetish scene, the leathermen, the educators who talk openly about boundaries, consent, and safety, are being algorithmically filtered out. We are not the danger. We are part of the antidote.

But let’s think harder. What this legislation proposes is not safety, it’s displacement. Not protection, but disconnection. It assumes, mistakenly, that by making the visible invisible, we prevent harm. But the internet doesn’t work like that. Teenagers don’t work like that. If they can’t find answers in the daylight, they’ll go looking in the dark.

Let me speak plainly: if queer youth, if questioning teens, if kids with no vocabulary yet for what they’re feeling, grow up in an internet stripped bare of complexity and diversity, they will not become safer. They will become more vulnerable. Because in the vacuum left by moderation, someone else will step in. Someone with an agenda. Someone who doesn’t care about their safety at all.

There are already signs. As Meta, TikTok, and X race to comply, their algorithms misfire in predictable ways. Queer content is disproportionately flagged. Fetish aesthetics are flattened into pornography. Leather is mistaken for threat. Meanwhile, the hateful material that the Act supposedly targets: neo-Nazi forums, alt-right recruitment pipelines, and extremist incel communities, proves far slipperier. The state, in its earnest attempt to clean up the web, scrubs at the edges where the light shines and forgets that the real danger festers in the shadows.

It’s worth remembering that most of us who inhabit queer or fetish spaces grew up under the shadow of silence. I remember, as a teenager, watching friends stumble toward self-discovery with no maps and no guides. Some fell prey to exploitation not because they saw too much, but because they were taught too little. They had no language for their desires, no models of healthy intimacy, no access to queer adult community. That silence was a kind of violence, and it was state-sanctioned.

We’re in danger of repeating the same mistake.

The Act’s most perverse achievement might be to position adult queer culture as itself a threat. It places us, those of us who wear leather, who use kink to explore and heal, who teach consent, who celebrate difference, into the same bucket as those who genuinely cause harm. That is not safety. That is scapegoating. It conflates visibility with danger and forgets that for many of us, visibility was the only safety we ever had.

There is no appetite in the present government for cultural nuance. While the Act was conceived under a framework of broad parliamentary support, its rollout now falls to an administration increasingly defined by populist dog-whistles and the encroaching influence of reactionary forces. We have a Prime Minister clinging to crumbling poll numbers with veiled appeals to nationalism, and the rise of the Reform UK party, whose culture warriors have made “wokeness” their enemy. In that climate, even the most well-intentioned legislation becomes vulnerable to repurposing.

The Online Safety Act may not have been born of bad faith, but its future depends on who holds the pen. Today, its interpretation lies in the hands of regulators and corporations under pressure to appease the most vocal critics, often the very voices who view queer culture, kink, or gender nonconformity as threats to moral order. What begins as a safeguarding tool risks becoming an instrument of quiet repression.

Already, we see how the blunt edge of policy is cutting away the subtlety of human experience. A man in leather becomes a risk factor. A post on consent gets flagged. A community group disappears from view. And all the while, the truly harmful actors, those promoting hate, misogyny, and extremism, become ever more adept at adapting and surviving. If we define harm only by surface aesthetics, we’ll always miss what’s festering beneath.

And we must be honest about the consequence. Age-gating tools will be circumvented. VPNs will flourish. Curiosity will not disappear; it will migrate to darker corners, to unmoderated forums where exploitation thrives unchecked. If we starve the daylight of complexity, we feed the shadows. We push the curious and the questioning into the arms of those only too happy to offer certainty—often in the form of control, abuse, or indoctrination.

This is not a plea to abandon online safety. It is a plea to implement it wisely, proportionately, and with regard for the diversity of adult life. To centre consent, context, and community, not just in algorithmic frameworks, but in policy decisions and platform design. We need more voices, not fewer. More light, not more filters. Safety does not have to mean silence.

Of all the communities threatened by this shift, it’s the gay fetish scene that feels the chill most keenly. We have always lived at the edges—subcultural, subversive, stitched into queer history through protest, pride, and pain. But we have also always been visible. Leathermen’s presence was a form of resistance: unapologetic masculinity, reimagined and reclaimed. Now, I fear that visibility is slipping away. Not through bans or crackdowns, but through quieter, more insidious means: algorithmic suppression, prudish moderation, and the relentless flattening of adult life online.

Without space to be seen, we cannot grow. We cannot reach those who need us. Curious young men, like I once was, searching for a mirror, searching for meaning, will find nothing but silence. The leather community survives on connection, on ritual, on mentorship, and pride passed hand to hand. If we are pushed underground once again, we do not simply lose followers, we lose the chance to heal the harm of those years we lived unauthentically. And we lose the promise of being found by someone else, who, like us, is simply looking for a way to belong.

We, the leathermen, the fetishists, the queers, the educators, the outliers, we will not disappear again without notice. If the Act is to be more than another tool of erasure, its application must match its ambition. Because someone, somewhere, still needs to see us.

And someone, somewhere, still needs to know it’s okay to be them.

Leave a comment