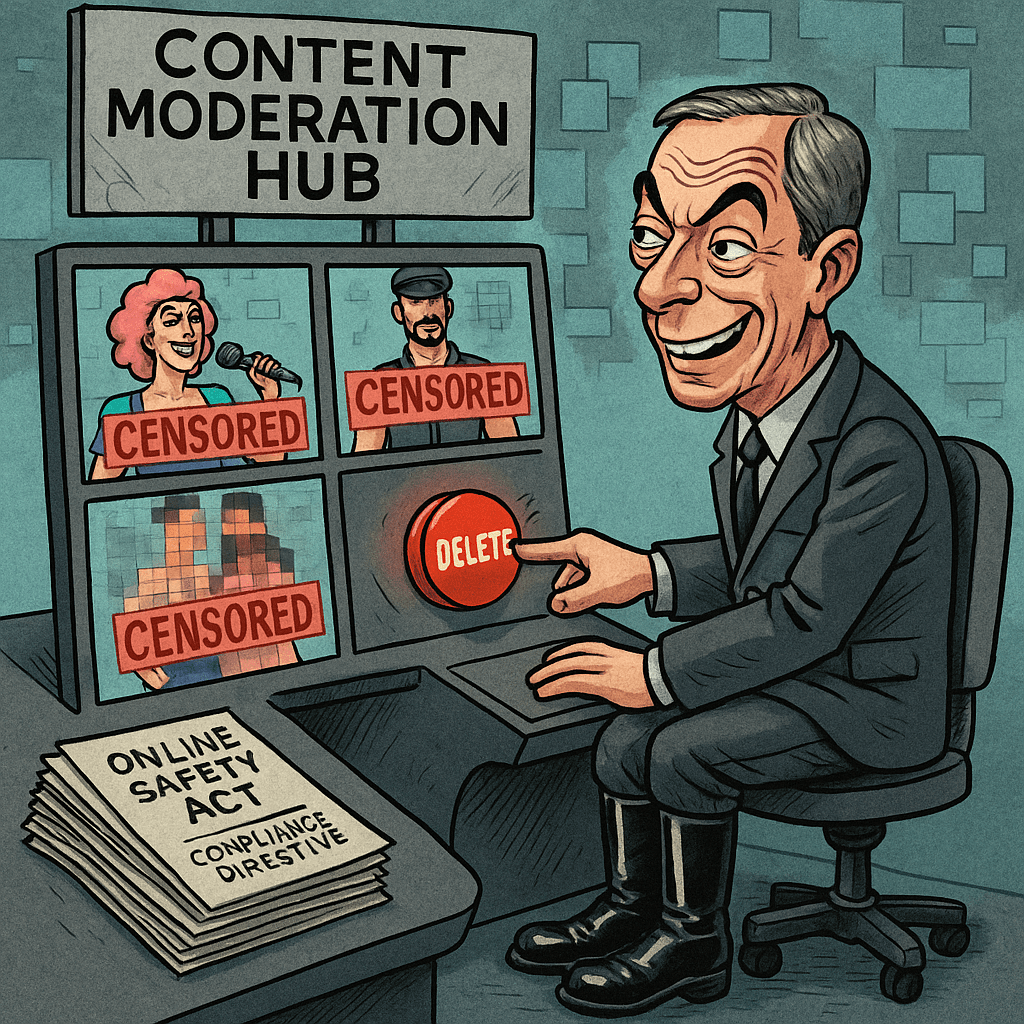

It is a strange thing, to find yourself nodding along with Nigel Farage. Stranger still when you’re a leatherman and advocate for LGBTQ+ rights. And yet, when it comes to the Online Safety Act, we appear, at least superficially, to agree: the legislation overreaches, it endangers free expression, and it threatens to scrub the internet of subcultural identity. But do not mistake shared criticism for shared cause. Because while I lament the erasure of queer, kink, and fetish spaces under algorithmic caution and legislative vagueness, Farage and Reform UK decry censorship of a very different kind: the curbing of hate speech, the restriction of race-baiting rhetoric, and the scrutiny of xenophobic propaganda.

The examples they cite when opposing the Act are telling: the supposed silencing of migration sceptics, the shadowbanning of gender-critical feminists, the inability to “tell the truth” about what’s “happening on our streets.” Not a word for the queer subcultures quietly disappearing from search results. No concern for trans educators facing takedowns. No recognition of the generational loss when queer content, already marginal, is rendered invisible by code, policy, and puritanism.

This is the danger we must confront with open eyes. The convergence of critique does not mean convergence of values. Reform UK’s defence of “free speech” is not about protecting queer storytelling, or preserving the messy, affirming ecosystem of LGBTQ+ expression online. It is a wedge issue, a rhetorical battering ram, deployed in service of a politics that has consistently undermined the rights of people like me.

Farage may not campaign to repeal same-sex marriage, but he has called it “wrong.” His party members have labelled Pride flags “degenerate” and sought to erase them from civic buildings. Reform-led councils have banned symbolic displays of LGBTQ+ solidarity under the false neutrality of flag policies, silencing communities under the pretext of unity. And while Reform now builds its own think tank, Resolute 1850, modelled on American evangelical playbooks, its ideological kin: the Christian Institute, and Christian Concern; have long fought to keep us out of classrooms, courthouses, and public life.

This is not the politics of liberation. It is the politics of polite repression.

We should ask ourselves: free speech for whom, and to what end? Farage wants free speech so he can say the uncomfortable things, without censure, without consequence, without being “cancelled.” But when those things resonate with what he calls the “silent majority,” when that sentiment is stoked into a wave of populist backlash, what happens next? Will he defend our right to be seen in leather, to speak openly about queer desire, to educate on consent, or to celebrate trans joy? Or will he ride that wave to wipe us out? Free speech is a principle, not a weapon, but in the hands of those who mistake dominance for dialogue, it quickly becomes a bludgeon. And make no mistake: once the wave crashes, it’s those of us on the margins who will be washed away first.

And looming in the background, casting a long and ominous shadow, is the spectre of Reform UK’s desire to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. Let me be clear: I am no slavish devotee of the status quo. The ECHR and its case law are not beyond criticism. Legal reform is long overdue, particularly in how rights are balanced and enforced in the context of modern digital life. But to tear up the Convention altogether, and replace it with a so-called British Bill of Rights, authored by Farage and his cohort, is not reform. It is a warning.

Who decides what counts as a right in this new order? Will it be the same party that wants to end gender recognition, silence dissenting flags, and expunge “woke ideology” from schools and local government? These are not people who seek to expand the sphere of liberty. They seek to redefine it in their image: narrow, majoritarian, and morally policed. For LGBTQI+ people, for migrants, for disabled activists, for anyone who has ever relied on rights as a shield against the state rather than a gift from it, this should be blood-curdlingly chilling.

We’ve seen this before. Section 28 didn’t ban being gay, but it banned being seen. It wasn’t criminalisation, it was erasure, in the name of protecting children. And the trauma it caused still ripples through generations of queer adults, silenced in classrooms and shamed into secrecy.

And it’s the ECHR that has slowly, steadily helped us reclaim ground. Article 8, the right to private and family life, was pivotal in cases like Goodwin v. United Kingdom (2002), which secured legal gender recognition for trans people. Article 10, the right to freedom of expression, was vital in Alekseyev v. Russia (2010), where the Court ruled that banning Pride marches in Moscow violated queer citizens’ rights to protest and be heard. Article 14, which prohibits discrimination, has underpinned a host of rulings against unequal age of consent laws, unjust dismissals, and homophobic policy enforcement. These aren’t abstract rights, they are precedents that protect our lives.

If we surrender these protections to a populist rewrite, what remains? A bill of rights written not to expand justice but to limit who it applies to. A legal framework designed not to safeguard minorities but to appease majoritarian anxieties. The ECHR was born from the ashes of fascism, a promise that the dignity of the few would not again be sacrificed to the fears of the many. That Nigel Farage and Reform UK now see it as an obstacle should tell you everything you need to know.

Yes, the past 15 years have bred malaise. Yes, people are angry. After austerity, Brexit, the sleaze, the inertia, and the sheer managerial mediocrity of our political class, the appetite for change is real, and justified. Labour, now tightly scripted and triangulated, offers more steadiness than inspiration. Many, particularly younger voters and the politically dispossessed, crave something bolder.

But in this craving lies danger. Reform UK presents itself as anti-establishment, anti-elite, anti-woke. It plays the populist game expertly, offering plain words and easy answers: scrap the Online Safety Act, fix the borders, cut the red tape. But populism’s promise is always cheap. It flatters your discontent while hollowing out the very freedoms it claims to protect.

There are no credible plans in Reform’s platform, only fury. No pathway to better rights, only the rollback of protections hard won. Its vision of free speech is not one where a trans teenager can find affirming content online, or where a leatherman can post with pride. It is one where dissenters to the new orthodoxy, be it queer, migrant, or feminist, are pushed once again to the margins. All under the banner of protecting children, traditions, and “real” Britain.

We must not fall for it.

Those of us critical of the Online Safety Act, and we are right to be, must remain vigilant. We must not mistake tactical agreement for moral alliance. We must advocate for an internet that protects without sanitising, that empowers without erasing, and that honours the pluralism of adult life. That means challenging Labour to do better. It means building coalitions that centre the marginalised, not court the mainstream. And it means exposing the populist wolves, however cleverly they dress as civil libertarians.

Farage and I may agree that the Act is flawed. But we do not agree on what should take its place.

I want a web that affirms my visibility. He wants a nation where people like me disappear again quietly. And in that difference lies the fight still to come.

Leave a comment